On my personal blog, I posted about my experience at the Kpong airfield in the Volta Region of Ghana. If you haven’t already, you can read that post here. Here is an excerpt:

Northeast of Accra, close to Lake Volta, the largest man-made lake in the world, there is a town called Kpong.

It is here that Jonathan Porter (aka Captain Yaw), a British expat, partnered with the local community to form an aviation and engineering school for girls (AvTech Academy), a flight school for anyone who wants to learn, and a humanitarian organization, Medicine on the Move (MoM), which uses planes to bring doctors and health education to villages that are inaccessible by road.

Patricia (see photo above) is 22 years old. She is the first woman to obtain Ghana’s National Pilots License. She is an engineer, a recipient of the Rotax Aircraft Engines certification. She knows how to fly and build planes. She’s the only certified female flight instructor teaching the National Pilots License in Ghana. When I met her, she was teaching a Norwegian oil industry engineer how to fly.

Any superlatives I use to describe my time at Kpong would be an understatement. I was truly blown away by my experience there. In this post, expect some camel drawing with the girls of AvTech Academy along with several insightful interviews. To start with, Jonathan Porter, the founder, and lead pilot Patricia Mawuli, were nice enough to answer a few questions about the various organizations that are operating in Kpong.

1) There are many non-profits and NGOs operating in Ghana and throughout sub-Saharan Africa. What makes your project unique? (with respect to both MoM and Avtech academy)

We believe in a sustainable solution. Let us be honest, most programmes aimed at helping folks are three to five year projects. Any parent will tell you that raising a child is more like a thirty five year project – and then some… even though results can be got in as little as eighteen years… EIGHTEEN – not THREE. If we were to ‘assess’ our children at three (or even five) and then cut the funding on them because it looked like they might make it in the world, we would be seen as ‘STUPID’ – but that is exactly what a THREE – FIVE project is.

Now, we understand that. Political cycles require that funding is short lived – for political cycles, and political careers are short lived. Therefore we set about creating a triangle of sustainability that makes our operations not only sustainable but self-perputating in terms of personnel and human endeavor collateral!!! For more on this, see this page.

2) What are some of the challenges in running MoM and Avtech Academy?

Not that many really, no more than any other operation. However, funding is always a challenge – and although we have our sustainability curve that we will be reached in the coming years, we could do with a little hand up to get onto that curve a little sooner so that we can focus more on the delivery with a solid, sustainable engine of change driving the propeller of health education to ensure changes in behaviour that will give rural communities the wings that they need for sustainable socio-economic development….

3) What is your vision for the future with respect to these projects?

Our big push in 2012 will be the ETCHE programme and the INCSI initiative, which we believe, linked with the MoM aerial support mechanisms will lead to a sea change in rural health outreach in developing nations.

4) When will we see a camel shaped plane?

Patricia says, the issue would be that the fuel tank would be large and heavy and the undercarriage only good in sand, as well as the lack of wings to provide lift may get in the way…. however, she adds, should you wish to provide funding for research – we are sure that we could ‘route it for a good cause’ …. and although it may not lead to a camel shaped plane, the principles and desired outcomes of camel drawing would be furthered, and more smiling faces may be found out there in the rural communities… all thanks to the principles of the Camel Man….

The Girls of AvTech Academy

These girls are learning how to fly and build planes. I feel privledged to know them. I spent the morning hanging out with the girls in the air traffic control tower (which they operated themselves) to get a better idea of their reasons for getting involved at Kpong airfield.

Juliet:

Lydia:

Emmanuella:

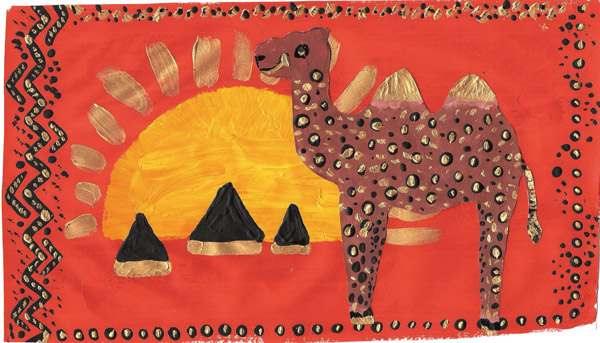

Of course, I didn’t leave Kpong without teaching the girls how to draw camels. I have not come across more enthusiastic or confident students.

Until July, all profits from the How to Draw Camels Ebook will be going towards Medicine on the Move. Few organizations have impressed me as much as this one.

Consider picking up the ebook if you haven’t already and be sure to check out the Medicine on the Move website as well as the MoM blog and the AvTech Academy blog.